Big Daddy Brown

By Hy Conrad

Sherman Holmes had been born and raised in Alabama and, despite his mania for Victorian England, had a deep, true affection for the American South. About once a year, usually on a warm spring weekend, he would gas up his antique Bentley and make the long pilgrimage back home.

Sherman himself was an orphan, but he had always kept in contact with his childhood neighbors, Big Daddy Brown and his clan. On one of his annual visits, the odd little detective found himself joining the Browns in every Alabamian’s favorite pastime, a picnic.

Sherman himself was an orphan, but he had always kept in contact with his childhood neighbors, Big Daddy Brown and his clan. On one of his annual visits, the odd little detective found himself joining the Browns in every Alabamian’s favorite pastime, a picnic.

The scene was a state park where the old southern family commandeered a picnic table. Big Daddy spread the tablecloth. Two of the grown children, Tiffany and Billy, unloaded the wicker baskets. The third, Julius, poured iced tea from a thermos, while Big Momma unpacked the crystal salt and pepper shakers and handed out cloth napkins. Sherman added his own touch, a candelabra topped with citronella candles to keep away the bugs.

Although he saw the Browns just once a year, Sherman felt he knew them intimately. Julius was close to his own age, while Tiffany and Billy, the twins, were a good ten years younger. None were married, as if forming a family of their own might be some sort of affront to the domineering father who controlled their lives.

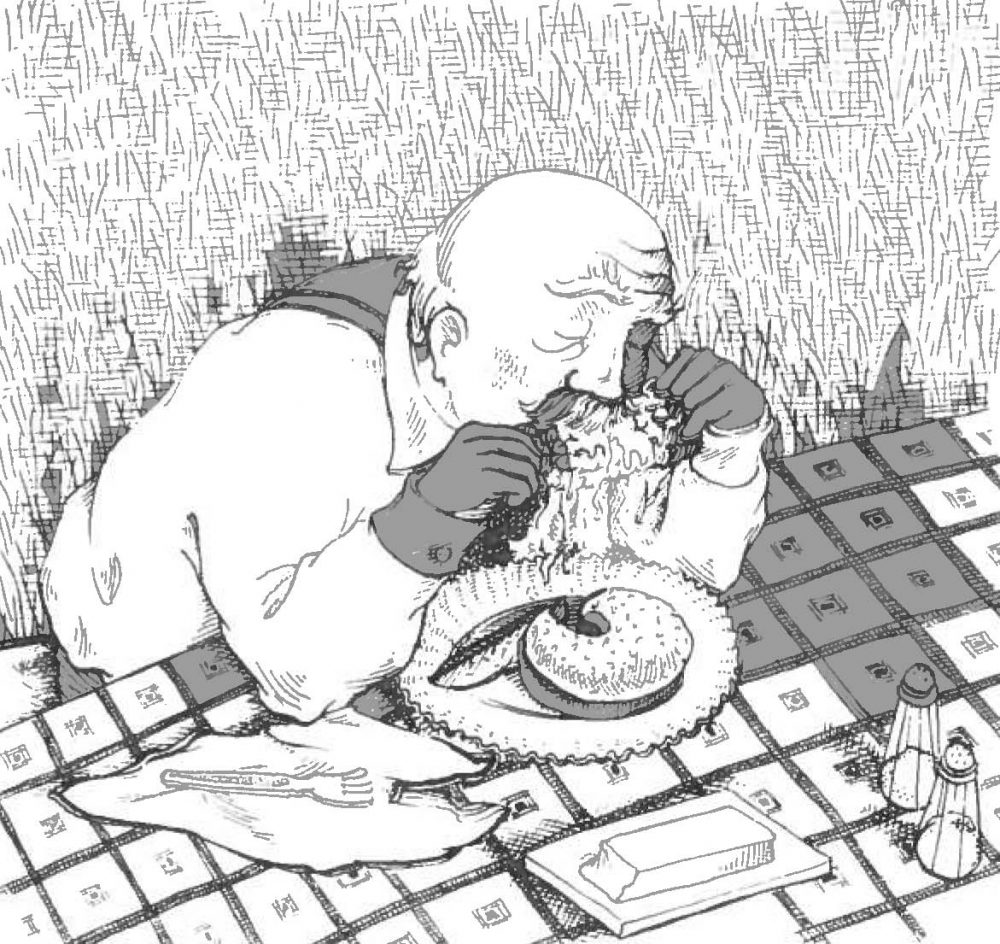

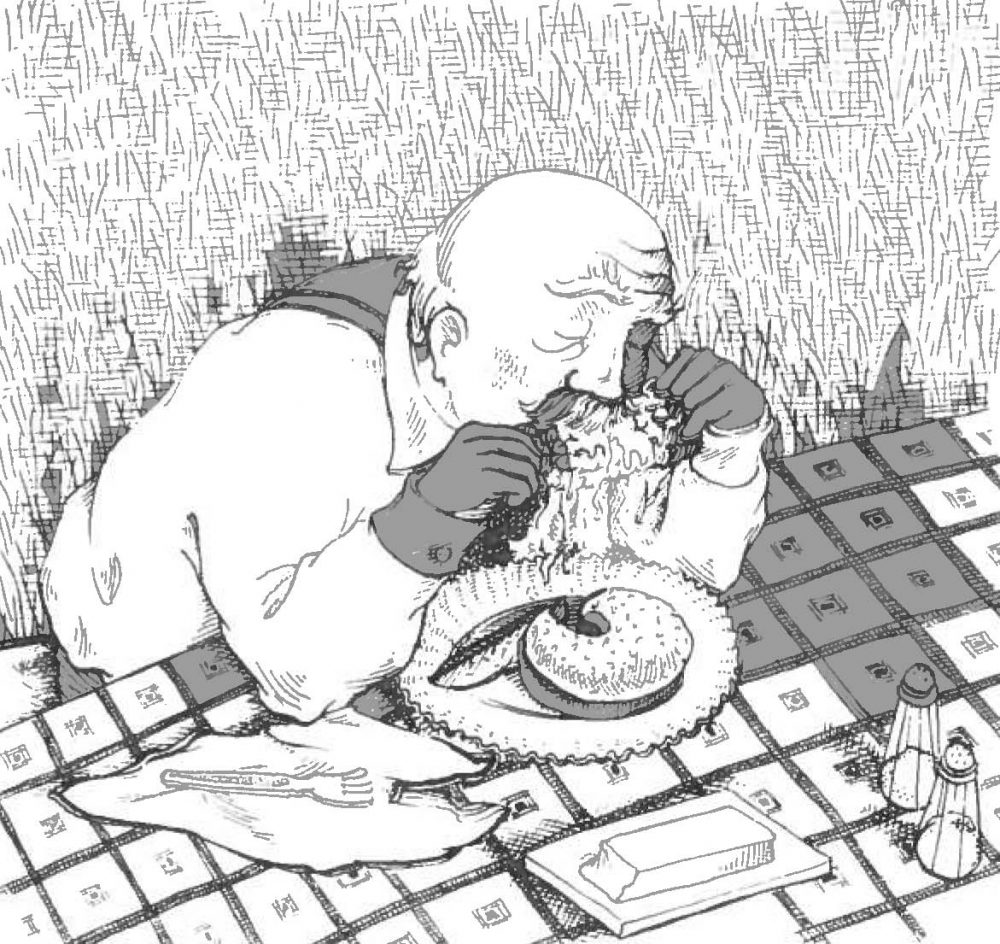

On the surface, the picnic resembled the dozen previous picnics he’d attended with the Browns. Billy flipped burgers on the grill. Julius kept everyone’s glass full. Tiffany and Big Momma hovered over the proceedings, doling out seconds and thirds, while Big Daddy slathered butter on his corn, spilling half of it on his plate and wiping the other half from his mouth with a napkin.

But something was wrong. The jokes were strained, the affection too forced, and Sherman’s sixth sense was kicking into gear. He tried to ignore it.

Big Daddy’s heart attack came suddenly, near the end of the meal. The elderly man’s fleshy face turned as white as his neatly trimmed mustache. His breathing grew heavy. Then he grasped his chest and collapsed backwards into the grass.

Sherman and Julius rushed to Big Daddy’s side. The others gathered around, looking on helplessly as the two men did their best to revive the stricken patriarch.

“He’s dead,” Julius whispered.

Tiffany ran off to call an ambulance, but everyone knew it would be too late.

“He’s had heart problems before,” Billy said, then turned to comfort his mother. “This was the best way to go, Momma, surrounded by family and eating his favorite food.”

Sherman had seen a few heart attacks in his time, and this certainly looked like one. He’d also seen more than a few poisonings.

Sherman glanced over at Big Daddy’s place at the table. His glass was half full of iced tea. His plate held the remains of potato salad, coleslaw, and the uneaten sliver of a hamburger bun. A clean but rumpled napkin sat beside the plate, right next to the crystal salt shaker.

The detective’s heart sank. Why did people try to get away with murder when he was around? It just didn’t make sense.

WHO KILLED BIG DADDY?

WHAT CLUE GAVE THE KILLER AWAY?

“I don’t want to turn you in,” Sherman said softly.

It was two days later and the family was walking away from the burial site, heading back to the funeral home’s limousine parked by the cemetery’s gravel road.

Sherman had maneuvered his way to Big Momma’s side. They were out of earshot of the others and would be for the next minute or two.

“I don’t want to turn you in,” he repeated. “Why did you do it?”

“For the kids,” said Big Momma. Her tone was eerily calm. “You saw how it was. All the time he pushed them down, controlled everything. Maybe now they can live their own lives. Me, too, “ she added as an afterthought.

“You poisoned his napkin.” Sherman had to show her that he knew. “Every time he went to wipe his mouth, he inhaled a little poison. Then, after he collapsed and no one was looking, you replaced it with a clean napkin. That’s what I noticed. A clean napkin – that should have been covered with butter.”

“You can’t prove it,” Big Momma said with a thin smile. “Even if you dig up the body and check it for poison, that napkin no longer exists. You can’t prove a thing.”